PORT HARCOURT - Once a vibrant fishing community in Port Harcourt, a city that has sprung up along the creeks of southern Nigeria, Okrika Waterfront is now a desolate polluted site.

Though perched on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, the water surrounding the community of some 10,000 people has turned black from decades of oil spills and illegal crude refining, forcing fishermen to relocate or search for other jobs.

The toxic legacy is part of a bleak landscape in Rivers State, where poverty has been exacerbated by an inflationary surge and many people are angry over the chaotic rollout of a currency swap.

The issues are at the forefront of this key electoral battleground as Nigeria votes on Saturday for a successor to its two-term president, Muhammadu Buhari.

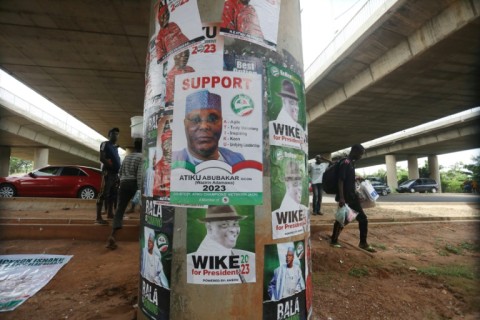

The three frontrunners are Bola Ahmed Tinubu of the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC), Atiku Abubakar of the main opposition's Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and outsider Peter Obi of the Labour Party.

In Okrika, as in much of Rivers State, voters are divided among all three.

Princewill Frank has lived for 15 years in the state capital, which is home to some 3.5 million people.

He worries his ballot won't count.

"I would like Obi to win but they will rig him out," said Frank, 57, walking past a woman sitting on the front steps of a house overlooking drains clogged with trash.

Preparing tiny tilapia fish to sell, 52-year-old Abigail Monday said she would vote "Atiku," as Abubakar is widely known, "to help make the country better."

- Cash crisis -

The south has long been a PDP stronghold.

But this year the dynamics have changed, in part because the powerful PDP governor, Nyesom Wike, has refused to endorse Abubakar, and because Obi has attracted unexpected grassroots support.

A cash crisis caused by a recent currency change is further complicating matters, with people now tempted to vote differently then how they would have previously, or not to vote at all.

On the buzzing Aggrey road, a dozen cars are queueing for petrol -- fuel scarcity has become a frequent problem in Nigeria including in the oil-rich region -- while large crowds of people gather outside banks desperate to get hold of some cash.

"My polling unit is six kilometres (almost four miles) away from my house. I want to vote but it depends if I can find cash to pay for transport," said Ruth Okechuwu, 43, who sells yams.

When the central bank replaced old naira notes with new ones in December, it issued a much smaller amount of bills in an effort to go cashless and reduce the amount of money outside the banking system.

But many Nigerians rely on cash for food and transport, making the policy highly unpopular.

"I've been to the bank five times but even when you wait for hours, they only give you 2,000 (about four dollars). I've stopped going now," said Okechuwu. "I'm a PDP woman but now I'm confused... I'm angry!"

- Linchpin state -

Winning Rivers State is crucial for any candidate aspiring to be president of Africa's most populous nation.

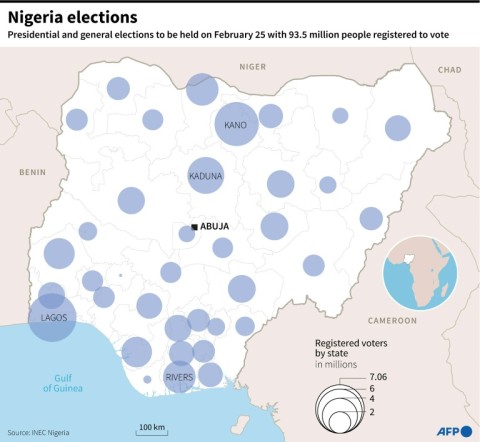

Nigeria's oil hub has the fourth largest pool of registered voters after Lagos, Kano and Kaduna.

It's also one of the richest regions, and for analyst Dengiyefa Angalapu of the Centre for Democracy and Development research group, "You cannot ignore a state that has that kind of internal revenue."

Nigeria's export earnings almost entirely depend on oil and gas, and Rivers has also long advocated for more control over the resources its land holds.

"Rivers can undermine national policies or actions and be a centre for anti-state mobilisation," said Tarila Marclint Ebiede, director of the Conflict Research Network West Africa network.

As the days ticked by to Saturday's vote, Wike kept his supporters guessing over which candidate he prefers for the presidency. Many suspect he supports Tinubu but backs PDP candidates for state and local seats.

Another destabilising factor in the region is the threat of violence, with former militants and thugs being "utilised informally to carry out actions of violence on behalf of political elites," Ebiede said.

"In highly contested states like Rivers, and all the states of the Niger Delta, you will see patterns of voter suppression and threats against voters and election officials."

lhd/pma/ri

By Louise Dewast