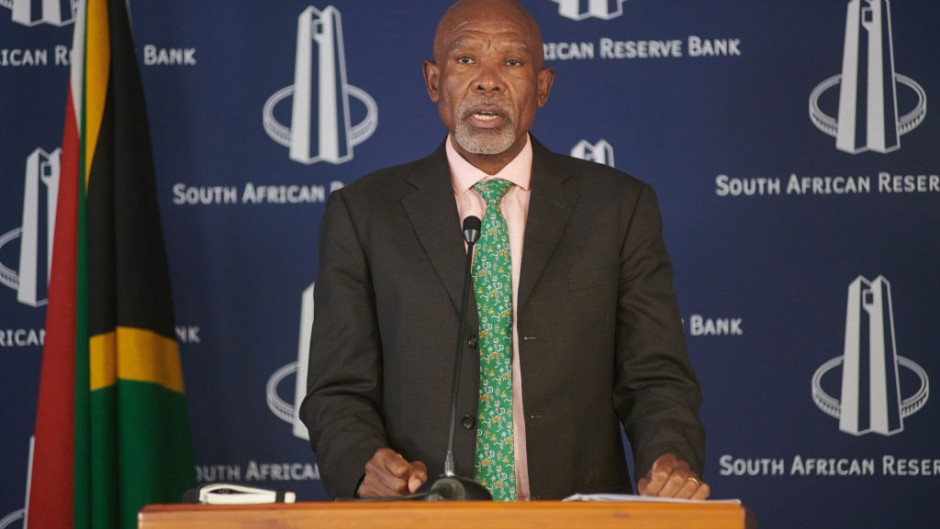

JOHANNESBURG - The Governor of the South African Reserve Bank, Lesetja Kganyago, has called for developing nations to be empowered to scrutinise the findings of ratings agencies.

He did so after a G20 meeting of finance chiefs in Washington recently.

Ratings agencies' credit scores for governments and companies play a role in determining where money is invested.

While there is some degree of transparency, final decisions are often made by private rating committees and are not easy to challenge.

The main rating agencies are Moody’s, S&P Global and Fitch Ratings.

Kganyago said developing countries should have more latitude in dealing with ratings agencies.

They should be able to review the data and methodology used to determine a country’s rating.

He added this could improve the borrowing costs for developing nations saddled with high debt-servicing costs.

Kganyago pointed out that developed countries would also benefit from a higher degree of transparency.

South Africa currently holds the presidency of the G20 and has identified debt sustainability for developing nations as a priority.

There have been some challenges. The first working group earlier this year failed to reach consensus.

According to Kganyago, this was due to the size of the G20 forum, the brevity of each G20 presidency, and the number of items on its agenda.

However, at the start of the latest meeting, a group of 165 organisations penned a letter to President Cyril Ramaphosa, criticising South Africa for not making sufficient progress on the issue of debt sustainability.

They urged Ramaphosa to push for reforms before South Africa hands the G20 presidency to the United States of America on 1 December.

The group has called for "the cancellation of all unsustainable and illegitimate debts, from all creditors."

It believes developing countries, in particular, should focus more of their budgets on education, health, gender equality and climate resilience.

South Africa is also in this trap. It sits with a debt-to-GDP ratio that, at 76%, is considered high for a developing country. It spends more than R1-billion a day on debt servicing costs, more than it does on health, education or policing.

It is a worldwide problem. According to the International Monetary Fund, global public debt is expected to rise to 123% of global GDP by 2029.

The finance ministers of the G20 did reach consensus, committing themselves to “further enhance debt sustainability”.

This included a “call to enhance debt transparency from all stakeholders, including private creditors”.